The young man in the airplane next to me, who I later learn is a student at a small Christian university outside of Denver, is clearly suffering from a serious upper respiratory infection, and just as clearly lacks even the most basic supplies for dealing with it. After he resorts to blowing his nose into his sweatshirt, noisily and productively, I offer him some tissues. That helps, for a while, but I nonetheless spend most of the four-hour flight from Philadelphia to Denver shying away from the armrest between us and doing my best to inhale in the other direction. I am under no illusions that either will protect me, but there are no other options on this packed flight.

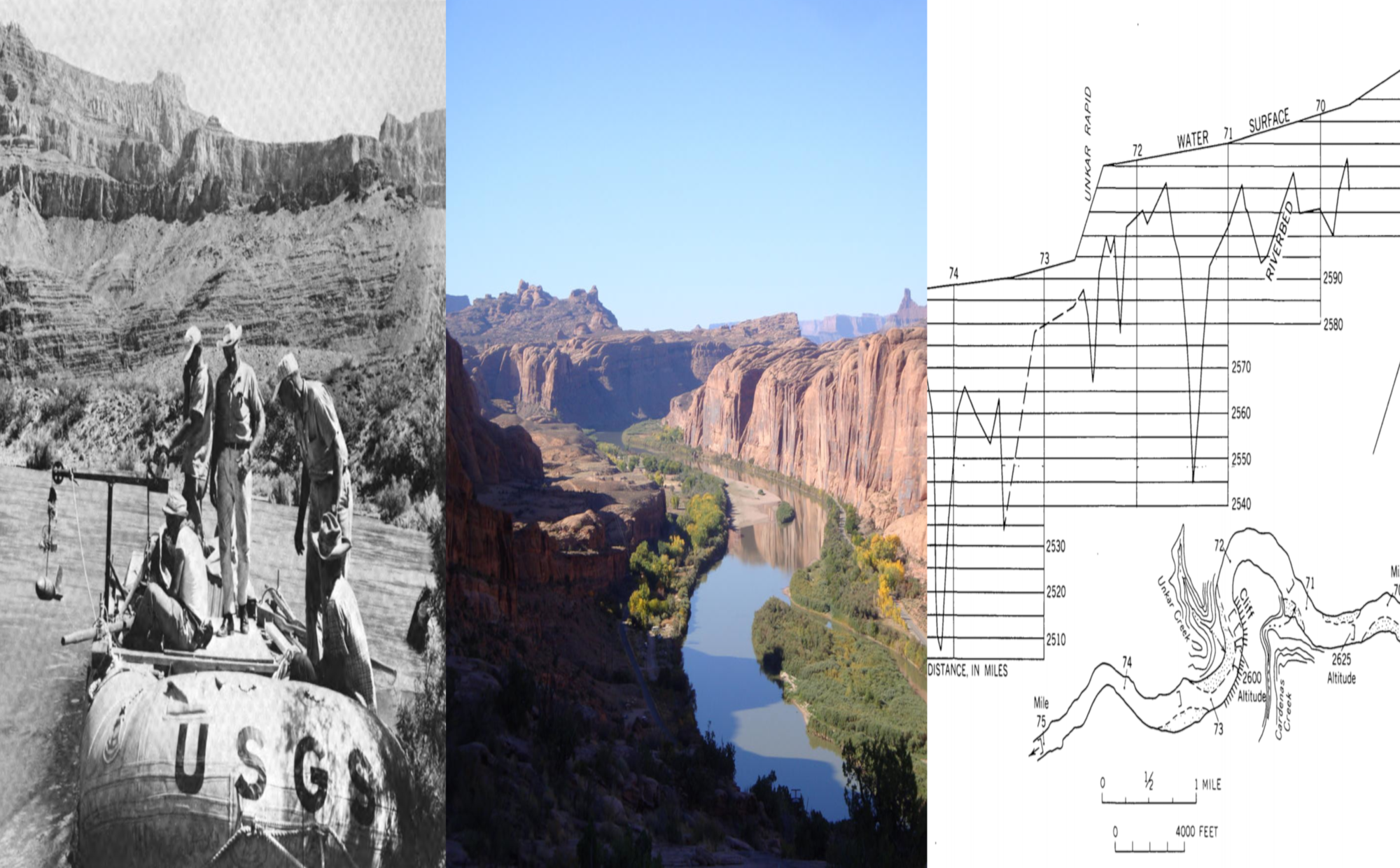

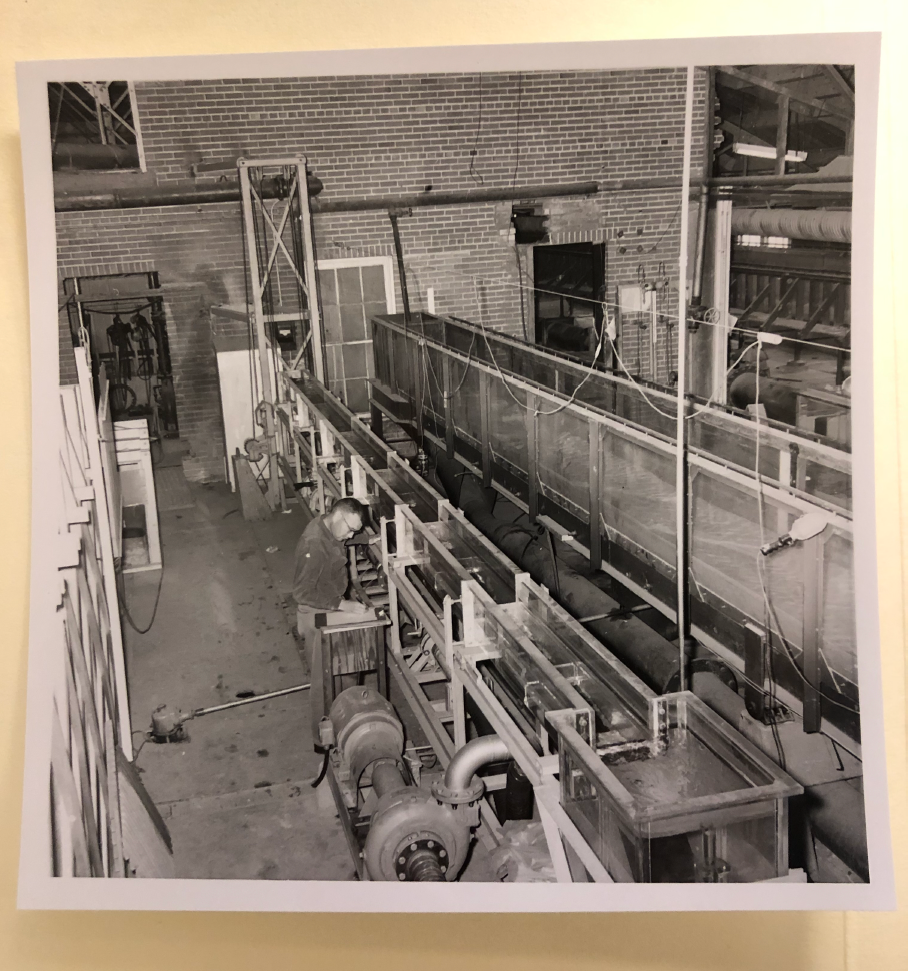

It is February 2020, and I am flying to Denver to make a short stop in Fort Collins, a little more than an hour’s drive north of the Denver airport, on my way to Phoenix to meet with colleagues involved in an interdisciplinary research collective on water issues. Fort Collins is the home of Colorado State University, where groundbreaking studies of the transportation of sediment by streams were carried out in experimental flumes in the 1950s and 1960s. My goal in stopping in Fort Collins is to gather as much information about those experiments as I can in the Water Resources Archive, which includes the papers of key figures such as Maurice Albertson, Everett Richardson, and Daryl Simons. Even though an impressive proportion of the Water Resources Archive records has been digitized, the records I am most interested in are still only available on paper.

With the help of the tremendously knowledgeable Patty Rettig and other CSU archivists, my highly compressed visit turns out to be quite productive. In addition to photos of the experimental flume apparatus (see below), I find extensive exchanges of letters between Luna Leopold and CSU researchers, including detailed discussions of the relevance of Ralph Bagnold’s theories of sediment transport to the experiments they are carrying out — something I had suspected I might find but wasn’t sure would justify the trip. It does, in spades. I also find fascinating material on subjects I hadn’t anticipated at all, including reams of documents relating to the work of CSU hydraulic engineers on the link canals constructed in Pakistan following the signing of the Indus Waters Treaty with India in 1960. As I return the last archival box to its cart and pack up my laptop, I have the feeling that this hastily planned stop-over has gone much better than I had any right to hope.

Unfortunately, that feeling doesn’t last long. A few minutes after I start my drive back to the Denver airport to catch my flight to Phoenix, a blizzard blows in, slowing traffic on Interstate 25 to a slippery, white-knuckled 15 or 20 miles per hour. Google Maps tells me I might gain a few minutes by shifting over to the frontage road, a detour that seems wise until I find myself at the bottom of an icy hill behind a row of wheel-spinning cars misled by the same advice. Back on the freeway after a hair-raising five-point U-turn, I see more than one car slide off the road in front of me. I begin to entertain morbid thoughts about how long I will last on the snack bar and half-empty bottle of water I have with me in the car. Even though I miss my flight, it’s an enormous relief when I finally hand over the keys to the rental car agency and take a seat on the shuttle to the terminal.

Ultimately, I suffer nothing worse than some anxious hours on the road, the expense of rebooking my missed flight for another a few hours later, and a too-short night’s sleep in Tempe. And, stressful as it was for me, the local news reports I read later make it seem like it was all in a normal winter day’s commute for Coloradans.

Nonetheless, my trip to Fort Collins, from the sneeze-filled flight to the snowy drive, is a reminder that the materiality and situatedness of the archive still matter, even as many archives race to digitize their holdings. Discovering new things about the past costs money, takes time, depends on labor (both that of others and oneself), and requires one’s bodily presence, which is not without its attendant risks. At the moment, with the coronavirus pandemic shuttering archives the world over (and threatening to transform “archive fever” from a playful and productive metaphor to an all-too-literal threat), the vast majority of historians have put such work on hold. But when the archives reopen, many of us will have to make decisions about how to move forward with our research, with a newly sharpened awareness of the costs and risks it entails.